Extended Harmony, and Tiger Repellent Drumming

Attention conservation notice: Almost 1000 words of follow-up to a post on an inter-blog dispute, complete with graphs and leaden sarcasm.

Some follow-up to the last post, in response to e-mails, and discussion elsewhere.

- Non-capitalist societies can and do, of course, also have lots of

inequality. So?

- I do not see why my aside about capitalism and state power should be the

least bit controversial. Since my libertarian friends seem more comfortable

with deduction from first principles than empirical observation, let's try it

this way. Capitalism needs private property. Since there will be disputes

about property, there must be an institution for settling those disputes

effectively. That institution is the state. (Yes, I know about

anarcho-capitalist ideas for private, market-driven courts and policing. These

would last about a week: at best, they would re-sort themselves into

territorial states, or more likely those doing the guard labor would ask

themselves what they guard should belong to someone else.) Capitalism thus

presumes a state which decides who owns what, and is (almost) unquestioningly

obeyed. Again: capitalism needs contracts, there will be disputes about

contracts, there must be an institution which can settle those disputes. Thus

capitalism presumes a state which can decide who owes what to whom, and force

them to pay. Capitalism with intellectual property is even more demanding:

copyright presumes a state exercising minute control over the content of all

modes of communication; patents presume a state exercising minute control over

processes of production and the use of knowledge. (And then we can get into

what the state has to do by way

of culture and education,

i.e., reshaping the mentality of the

population.) When such powers are used stupidly or capriciously, capitalism

suffers, but when such powers are absent, capitalism does not exist.

Now, continuing with the theme of harmonizing means and ends, if you want capitalism, but you find a state that powerful very scary (as you have every right to do), then you have a problem. You might, on reflection, favor some other economic system which does not require such a powerful state. (This is not a popular option, save among marginal advocates of rural poverty and idiocy.) You might, on reflection, decide that such power is perfectly A-OK, so long as it's used for ends you approve of and there's no danger of the people taking over. (Hence Hayek's anti-democratic political ideas, and viewing Pinochet's reign of terror as less damaging to [what he saw as] liberal values than the British National Health Service.) Or you might try to find ways of taming or domesticating state power, of civilizing it. (I think that has a pretty good track-record, but who knows how long we can keep it up?) What you cannot do, with any intellectual honesty or even hope of getting what you want, is pretend that capitalism can work without a powerful, competent and intrusive state. As Ernest Gellner once wrote, "Political control of economic life is not the consummation of world history, the fulfilment of destiny, or the imposition of righteousness; it is a painful necessity."

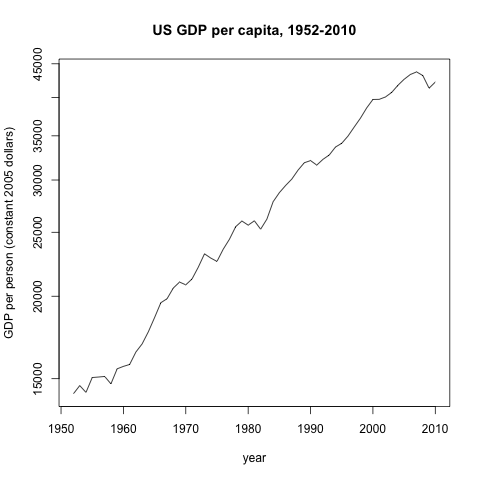

- I should have made clearer that the policies which have been sold over the

last few decade as enhancing economic growth have little show for themselves on

that score. A crude but still illuminating way to see this is simply to plot

GDP per person over time, adjusted for inflation:

Data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank's FRED service: GDP from the GDPCA series, population from the POP series. The plot starts at 1952 because that's when the population series does.

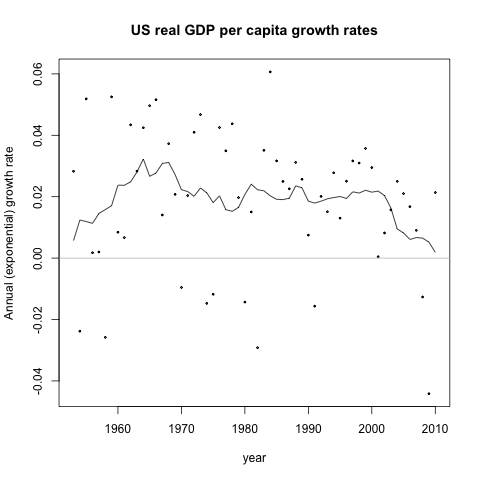

Annual exponential growth rates from the previous figure: yearly values (dots) and an 11-year moving average (black line). (The correlation time of the growth rate series is about 3.5 years.)

What these graphs bring to mind is the ancient joke where a new doctor is examining a patient in an insane asylum. The lunatic is compulsively banging on a drum, and the doctor asks why. "To repel the tigers, of course." Doctor: "Tigers? There are no tigers for thousands of miles!" Lunatic: "You see how well it works." If you want to say that the more deregulatory, capitalism-unleashed direction in which policy has moved since the 1980s (or even the late 1970s) is growth-enhancing, you can't point to an acceleration of growth, since there hasn't been any (pace Eugene Fama and John Taylor). Instead, you have to argue, counter-factually, that without those policy changes, growth would have slowed down (even more than it did); that pounding those drums drove away the tigers of stagnation. It's not completely illogical to try to explain a more-or-less constant growth rate with a variable policy regime, but you need some story about what other variables policy is compensating for, and indeed a story about why the compensation is so close.At a finer-grained level, you can look at performance over the business cycle, and again see that the new policy regime doesn't deliver any more aggregate growth. It certainly doesn't lead to faster productivity growth (again, despite claims to the contrary). But one thing which has changed is that aggregate growth does a lot less for most people than it used to. Again, you could tell a counter-factual stories about how all of these would be much worse without those policies, but by this point you are claiming that your drumming repels not just tigers but also snow leopards, elephants, and Glyptodon.

Manual trackback: Agnostic Liberal; Doubting Marcus

Posted at August 01, 2011 09:50 | permanent link