Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, April 2020

Attention conservation notice: I have no taste, and no qualifications to opine on American civil rights law, literary criticism, the psychology of reading, the literary ambitions of Karl Marx, Islamic history, or even, really, mathematical models of epidemic disease.

- Lisa Sattenspiel with Alun Lloyd, The Geographic Spread of Infectious Diseases: Models and Applications [JSTOR]

- This is an fine shorter book (~300 pp.) on mathematical descriptions and

models of how contagious diseases spread over space and time. It alternates

between chapters which lay out classes of models and mathematical tools, and

more empirical chapters which cover specific diseases. The models start with

the basic, a-spatial SIR model and its variants (ch. 2), then model expansions

which run an SIR model at each spatial location and couple them (ch. 4),

network models (ch. 6), and approaches from geographers, emphasizing map-making

and regression-style modeling (ch. 8), which is where I learned the most. The

introductory chapters do a good job of laying out the basic concepts and

behavior of epidemic models, so in principle no previous background is required

to read this, beyond upper-level-undergrad or beginning-grad mathematical

competence. (There are no proofs, and only really elementary derivations, but

the reader is expected to be familiar with differential equations, basic

probability, and the idea of an eigenvalue of a matrix.)

- The applications chapters cover, in order, influenza (especially seasonal influenza but also the 20th century pandemics), measles, foot-and-mouth disease, and SARS. A nice feature of the latter two chapters is a careful, somewhat skeptical look at how much policy-makers relied on mathematical models, and the extent to which such reliance helped.

- This was on my stack to read as preparation for revising the "Data Over Space and Time" course, but prioritized by recent events; recommended. §

- The applications chapters cover, in order, influenza (especially seasonal influenza but also the 20th century pandemics), measles, foot-and-mouth disease, and SARS. A nice feature of the latter two chapters is a careful, somewhat skeptical look at how much policy-makers relied on mathematical models, and the extent to which such reliance helped.

- Peter Diggle, Kung-Yee Liang and Scott L. Zeger, Analysis of Longitudinal Data

- A standard text on longitudinal data analysis for lo these many years now,

and deservedly so. The following notes are based on (finally) reading my copy

of the first, 1994 edition all the way through; I have not had the chance to

read the second edition (2002, paperback 2013).

- What statisticians (especially biostatisticians) call "longitudinal" data is basically what econometricians call "panel" data: there are a bunch of people (or animals or factories, generically "units"), and we collect the same information for each of them, but we do it repeatedly, over time. (Different units may be measured at different times, and not every variable may be measured for every unit at every time.) We typically assume no interaction between the units. In symbols, then, for unit $i$ at time $t_{ij}$ we measure $Y_{ij}$ (which may be a vector, even a vector with some missing coordinates), there are covariates $X_{ij}$ (which may be constant over time within a unit or not), and we assume independence between $Y_{i}$ and $Y_{j}$.

- From the point of view of someone trained to approach everything as a regression of dependent variables on independent, "explanatory" variables, here a regression of $Y_{ij}$ on $X_{ij}$, longitudinal data is a tremendous headache, because all the observations within a unit are dependent, even when we condition on the independent variable. In the simple linear-model situation, we'd write $Y_{ij} = \beta_0 + \beta \cdot X_{ij} + \epsilon_{ij}$, but with the caveat that $\epsilon_{ij}$ and $\epsilon_{ik}$ are not independent, but have some covariance. (Generalized linear models are also treated extensively here, to handle binary and count data.) This means that the usual formulas for standard errors, confidence intervals, etc., are all wrong. This point of view, which the book calls that of "marginal modeling", is the implied starting point for the reader, and I think it's fair to say it gets most of the attention. The key is to come up with estimates of the covariance of the $\epsilon$s, perhaps starting from a very rough "working" covariance model, or even from looking at the residuals of a model which ignores covariance in the first place, and then using weighted least squares and robust standard errors to improve the inferences. There's a chapter on why ANOVA is not enough, which I suspect arose from students wanting to know why they couldn't just do ANOVA for everything.

- One source of within-unit covariance is "random effects". The simplest form of this replaces the model I wrote above with $Y_{ij} = \beta_0 + Z_i + \beta \cdot X_{ij} + \epsilon_{ij}$, where now the $\epsilon_{ij}$ are uncorrelated over time (as in ordinary regression), and $Z_i$ is a unit-specific random variable. This implies that a unit which is above the regression line at one time will tend to also be above the regression line at another, creating a constant-over-time covariance structure. Equivalently, each unit has its own intercept, but those intercepts are clustered around some over-all $\beta_0$. This simple idea can be elaborated into letting the regression coefficients in $\beta$ also fluctuate from unit to unit. The book gives a pretty thorough treatment of estimation and inference for these random-effect models for longitudinal data, but doesn't look (much) at how to combine random effects with correlations in the $\epsilon$s, or at model-checking.

- The book also considers a third point of view, that of "transition modeling", which is the one I find most congenial, as someone brought up in the dynamical systems / stochastic process tradition. This is to see longitudinal data as a pile of short, independent time series, so the natural thing to do is to pool the information to get a better estimate of the process, and/or to estimate the latent state of individual trajectories. That is, we try to learn $P(Y_{i(j+1)}|Y_{ij}, X_{ij})$ (or condition on more history, as needed), and/or $P(S_{ij}|Y_{ij}, X_{ij})$ for some latent state $S$ that's reflected in the $Y$s. I think this is much more straightforward and meaningful than ad hoc covariance functions for the noise, but I also realize that's my version of "So, why does <your field> need a whole journal, anyway?".

- (For linear models with Gaussian noise, there are ways of inter-relating marginal models, random effects models and transition modeling, but these correspondences break down in more general situations, and the book is careful to explain why.)

- The implied reader here has a pretty firm grounding in linear regression modeling, and general undergrad-level probability and statistical inference, but no previous experience with time series. There are lots of real-data examples, mostly bio-statistical, where the modeling is always done in a way which tries to actually illuminate the scientific (or medical or agricultural) problem at hand. (This extends to a whole chapter on missing data, and the particular ways it goes missing in longitudinal data collection.) Doing so helps the reader implicitly learn better statistical craft than just just treating the data as piles of numbers to be fed into S. As the fact that I wrote "S" and not "R" in the last sentence indicates, the computing is now a bit antiquated, but replicating the analyses in R will build character. §

- What statisticians (especially biostatisticians) call "longitudinal" data is basically what econometricians call "panel" data: there are a bunch of people (or animals or factories, generically "units"), and we collect the same information for each of them, but we do it repeatedly, over time. (Different units may be measured at different times, and not every variable may be measured for every unit at every time.) We typically assume no interaction between the units. In symbols, then, for unit $i$ at time $t_{ij}$ we measure $Y_{ij}$ (which may be a vector, even a vector with some missing coordinates), there are covariates $X_{ij}$ (which may be constant over time within a unit or not), and we assume independence between $Y_{i}$ and $Y_{j}$.

- Sherri Cook Woosley, Walking Through Fire

- Mind candy. This is a well-written the-magic-returns-and-our-world-changes contemporary fantasy, clearly setting up what should ordinarily be an enjoyable series, but of course the pandemic happened in the middle of my reading it. Suddenly, my reaction a vision of the post-apocalyptic mid-Atlantic states being balkanized by squabbling Mesopotamian gods is less "I'm amused by what she's done to that all-too-familiar stretch of I-70" and more "Not now, Tiamat, not now". (Picked up on Walter Jon Williams's recommendation.) §

- Richard Thompson Ford, Rights Gone Wrong: How Law Corrupts the Struggle for Equality

- It is, of course, beyond my competence to comment on Ford's interpretation

of the law. But he has a lot of persuasive-to-me things to say about how

approaching social injustice as a matter of violating individual rights is not

always wise or effective, particularly when what's at stake is, say, a

complicated, multi-causal pattern of differences in outcomes rather than

outright bigotry: "Civil rights are remarkably effective against overt

prejudice perpetrated by identifiable bigots. But they have proven impotent

against today's most severe social injustices, which involve covert and

repressed prejudice or the innocent perpetuation of past prejudice."

- Though Ford doesn't use this parable, many of my readers will understand if I put things in the following way. Back when the ink was still wet on the Civil Rights acts, Thomas Schelling developed a deservedly-famous little model of how a slight preference for similar neighbors --- really, not wanting to be in too small a minority locally --- would lead an integrated residential pattern to unravel into segregated regions*. (IIRC, Ford mentions this model in other books, but not here.) Now suppose we prepare the Schelling model in a state of enforced segregation, and then remove the constraint. We'll find some desegregation, but the dynamics will lead to there still being a lot of segregation. Ford sees that Schelling-world would have a real social problem, but doesn't see who could be usefully sued, or protested, to make it better.

- Naturally, Ford is a lot sketchier about what would be a better way to make progress towards equality.

- Ford's page for the book links to several excerpts. §

- *: Schelling, not being an idiot or an apologist, did not think that this was the main explanation of US residential segregation circa 1970: "the subject of this paper might be put in third place" behind "organized action" on behalf of segregation, and economic inequality between the races [Schelling 1971, pp. 144--145]. (In this he was wiser than some later, lesser economists.) But he was right to point to it as an obstacle to integration which would be there if and when "organized action" and economic inequality were eliminated. ("Still, in a matter as important as racial segregation in the United States, even third place deserves attention.") ^

- Though Ford doesn't use this parable, many of my readers will understand if I put things in the following way. Back when the ink was still wet on the Civil Rights acts, Thomas Schelling developed a deservedly-famous little model of how a slight preference for similar neighbors --- really, not wanting to be in too small a minority locally --- would lead an integrated residential pattern to unravel into segregated regions*. (IIRC, Ford mentions this model in other books, but not here.) Now suppose we prepare the Schelling model in a state of enforced segregation, and then remove the constraint. We'll find some desegregation, but the dynamics will lead to there still being a lot of segregation. Ford sees that Schelling-world would have a real social problem, but doesn't see who could be usefully sued, or protested, to make it better.

- D. J. Daley and J. Gani, Epidemic Modelling: An Introduction

- Briskly written and now-classic first textbook on epidemic models,

especially compartment-type models. I think it would still make a good

introduction, and I plan to borrow from it freely the next time I teach these

models. (The measles data sets!) But there's a lot more emphasis on getting

exact or nearly-exact solutions, by heroic exercises in manipulating

probability generating functions, Laplace transforms, etc., than I think is

really warranted, or at least useful for my sort of audience. (*) And of

course, being from 1999, a lot of interesting stuff has been done since!

§

- *: It's also a little bit curious, because by 1960, Bartlett was very much an advocate of the power of simulations in this field, and they're certainly very familiar with his work. But perhaps my own feeling that if we can't get clean theoretical results then we might as well just simulate for all the insight approximate Laplace transforms give us reflects generational turn-over, or even just a personal lack of imagination on my part.

- William Clare Roberts, Marx's Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital [JSTOR]

- I'm not sure what to make of this one.

- Roberts argues that Marx modeled the literary structure of Capital on Dante's Inferno, with the progression through the different kinds of sins in the Inferno mirroring the stages of Marx's exposition of how capitalism works and why it's so awful, from incontinence (because everyone is at the mercy of market forces, no one can really show steadiness of will) to force and fraud to betrayal. This seems pretty weak and forced to me. The best that Roberts can point to, by way of specific textual evidence, is Marx's general enthusiasm for Dante in his letters, and a handful of classical allusions in Capital, so this mostly rests on how convincing you find Roberts's parallels between the order in which Marx anatomizes capitalism, and the order in which Dante see sins being punished. These aren't the worst literary parallels I've seen, but aren't compelling either. The other unusual aspect of Roberts's Marx* is that he's a rather unorthodox republican, with a strong belief in freedom as non-domination. I actually find this more persuasive than the Dante, but I also wonder how much "republicanism", in this sense, was an actual historical phenomenon, as opposed to a late 20th/early 21st century ideology that's been projected back on to the past... A third aspect of Roberts's exposition of Capital is his emphasis on how Marx was arguing with followers of other early socialists (especially Proudhon and Owen), which leads Roberts to want to trace parts of Capital to Marx counting coup on his opponents by turning their rhetoric or ideas against them. (Roberts also keeps sniping, from his footnotes, at Jon Elster and G. A. Cohen, but sniping footnotes are if anything a homage to Uncle Karl.)

- I can't say I found this persuasive (though, really, I don't know enough to judge), but Roberts's Marx is certainly an interesting construction, and I did learn a lot about 19th century socialists other than Marx.

- --- Reading this leads me to some doubtless-trite reflections on difficulties --- you might even say "contradictions" --- inherent in advancing a novel interpretation of a work which is already well-known and influential. Precisely because it's a novel interpretation, you have to be saying that everybody else has been mis-understanding the book all this time. This in turn implies that (A) the book as has been influential because of a mis-interpretation, and (B) that the author failed to communicate. Both of which could be true. But then it's really the mis-reading (or mis-readings) which have been influential, not the correctly-understood work. And even great authors are certainly capable of failing to get their point across**, just like other writers. But surely both (A) and (B) should be seen as implausible, precisely because the work in question is well-known and influential, and they should become more and more implausible over time. So one would need either extremely persuasive evidence for the new interpretation in its own right, or to make special cases for (A) and/or (B) themselves. I guess there would be an exception for a claim to be re-discovering a correct interpretation, which used to be common but has been lost, but then I'd want to see evidence that the book did, in fact, use to be interpreted that way, and ideally an explanation for how that knowledge came to be lost. (To be clear, Roberts is not saying that everyone used to realize Capital was modeled on the Inferno, etc.) §

- *: Roberts also offers a new-to-me twist on the sense in which Marx held a labor theory of value. This turns on the "socially necessary" part of the value of a commodity being the labor time socially necessary to produce it. For Marx, according to Roberts, there literally was no way of determining how much labor was socially necessary to produce a commodity, other than to see what value it could realize in exchange. Roberts's thought is that if (say) there is a glut of abaci, so that each abacus fetches fewer yards of linen, coats, bottles of whiskey, Bibles, etc., than before, that is what tells us that not all of the labor which went in to making abaci was in fact socially necessary. Whatever its merits as a theory of value in its own right, I have a hard time squaring this with what Marx says about how supply and demand make prices fluctuate around values, and indeed the general tenor of the texts. But I lack the time, and the will-power, to examine all the passages Roberts cites in support of this, compare them with all the others which might seem to point in other directions, and figure out what Marx had in mind. I.e., I am not a scholar of Marx, and didn't I warn you that you were probably wasting your time reading this? ^

- **: For instance, since Marx's discussion of "the fetishism of commodities" in Capital has perplexed readers, and divided interpreters, essentially ever since it was published, I think we can agree that whatever he had in mind, he failed to get it across clearly. My hunch is that he hit upon a kind of murkiness here which is actually attractive, and keeps people coming back to this bit, feeling that there must be a way to make sense of it. In my more cynical moments, I wonder if Marx really had any clear idea in mind here. ^

- Roberts argues that Marx modeled the literary structure of Capital on Dante's Inferno, with the progression through the different kinds of sins in the Inferno mirroring the stages of Marx's exposition of how capitalism works and why it's so awful, from incontinence (because everyone is at the mercy of market forces, no one can really show steadiness of will) to force and fraud to betrayal. This seems pretty weak and forced to me. The best that Roberts can point to, by way of specific textual evidence, is Marx's general enthusiasm for Dante in his letters, and a handful of classical allusions in Capital, so this mostly rests on how convincing you find Roberts's parallels between the order in which Marx anatomizes capitalism, and the order in which Dante see sins being punished. These aren't the worst literary parallels I've seen, but aren't compelling either. The other unusual aspect of Roberts's Marx* is that he's a rather unorthodox republican, with a strong belief in freedom as non-domination. I actually find this more persuasive than the Dante, but I also wonder how much "republicanism", in this sense, was an actual historical phenomenon, as opposed to a late 20th/early 21st century ideology that's been projected back on to the past... A third aspect of Roberts's exposition of Capital is his emphasis on how Marx was arguing with followers of other early socialists (especially Proudhon and Owen), which leads Roberts to want to trace parts of Capital to Marx counting coup on his opponents by turning their rhetoric or ideas against them. (Roberts also keeps sniping, from his footnotes, at Jon Elster and G. A. Cohen, but sniping footnotes are if anything a homage to Uncle Karl.)

- David Koepp, Cold Storage

- Mind candy: parasite porn thriller. Engaging, but there are bits where I found myself rooting for the parasite. §

- Anna Lee Huber, A Grave Matter and As Death Draws Near

- Mind-candy historical mysteries. The fact that I tracked down volumes 3 and 5 of a series I've been reading out of order should tell you that I enjoy them... (Previously.) §

- John Billheimer, Dismal Mountain and Drybone Hollow

- Mind-candy mysteries, in which a consulting transport planner returns to his home in rural West Virginia to deal with family and rural decay. (Previously.) §

- Barbara Paul, Your Eyelids Are Growing Heavy

- Mind candy: Pittsburgh mystery from 1981, which begins with the matter-of-factly unflappable heroine waking up on a local golf course with no memory of how she got there, and builds to a complicated and fast-moving story. I admit I got an extra kick from the fact that it takes place in, largely, neighborhoods I know very well --- I walk over that golf course to work, have shopped at the fancy grocery store around the corner from the heroine's apartment, etc. --- but I think it'd be enjoyable even if you didn't care about Pittsburgh. §

- A. E. Stallings, Archaic Smile

- An early (1999) collection by a favorite poet, saved up for an April. It

turns out to be highly preoccupied with death and the underworld:

"Watching the Vulture at the Road Kill"

§You know Death by his leisure --- take

The time we saw the vulure make

His slow, hot-air-balloon descent

To a possum smashed beside the pavement.

We stopped the car to watch. Too close.

He bounced his moon-walk bounce and rose

With a shrug up to the kudzu sleeve

Of a pine, to wait for us to leave.

What else can afford to linger?

The eagle has his trigger-finger,

Quails and doves their shell-shocked nerves---

There is no peace but scavengers. - Richard W. Bulliet, Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quantitative History [ACLS Humanities E-Books] and Islam: The View from the Edge

- The first of these books is an ingenious undertaking in using historical

sources to shed light on something they weren't meant for. The second book

takes the conclusions of the first as the starting point for an interesting

revision of conventional views of Islamic history.

- First book first. Biographical dictionaries were, interestingly enough, a widely-cultivated genre in many pre-modern Islamic countries. Each of these would give a large number of biographies of people (usually men) who were eminent or remarkable in some respect, such as religious scholars in a particular city or district. Part of those biographies would of course be the full name of the figure, which, in Arabic, included a chain of patronymics, of the form "A, the father of Z, the son of B, the son of C, ... the son of M". (Thus the pioneering social scientist generally known in English as "ibn Khaldun" was more properly 'Abd-ar-Rahmân Abû Zayd ibn Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldûn, 'Abd-ar--Rahmân, the father of Zayd, the son of Muhammad, the son of Muhammad, the son of Khaldûn.) Bulliet's starting point is to suppose that the first appearance of an Arabic and especially of a Quranic name in this chain marks the family's conversion to Islam. (As a Persianist, he knows very well that later Muslims had little compunction about naming their children, say, Rustam or Tahmina.) Since the biographical dictionaries give dates, at least dates of death, with some reassonable-sounding guesses about the length of generations, typical age of conversion, and so on, this lets him work backwards to the approximate date of conversion of each patrilineage. (Since the same biographical dictionary will often contain multiple entries for relatives, one would want to (i) cross-check conversion dates, and (ii) only count each conversion once; I believe Bulliet does so but I can't find the passage.)

- You can then chart the fraction of all known conversions which took place in a given time window. This is what Bulliet gets when he does this for "Iran", i.e., all Persian-speaking areas:

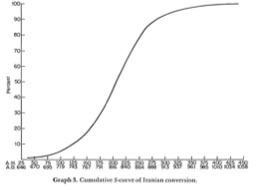

This looks even more impressive when plotted cumulatively:

(Click on either image to embiggen.)- As Bulliet says, this is a textbook-quality fit to a logistic curve, which is exactly what you'd expect from the simplest diffusion-of-innovations model. (In terms of epidemic models, an SI model.) I am legitimately impressed, and will certainly use this the next time I teach that subject. [Update: So I did.] (Though I have also acquired enough of the statistician's carping, quibbling spirit that I'd want to see how much different choices about things like generation time would alter his results.)

- Bulliet goes on to construct similar curves for other parts of the Muslim world --- Spain, Egypt, Syria, Iraq --- but admits that the data aren't as great, partly because of the quality of the sources, and partly because it's harder to use linguistic clues to identify conversions in those regions. (As he says, Spain is an exception here.) These are broadly similar in their shape, though timing is a bit different from one place to another.

- The historical interpretation Bulliet builds on these findings is given briefly in Conversion, and considerably more elaborated in View from the Edge. This is that the Muslim community in fact grew fairly slowly at first, even when large territories had been incorporated into the caliphate. The new Muslims, he argues, tended to move to cities which were sites (initially) of Muslim garrisons (sometimes being founded as such), creating an unusually urban religious environment. Figuring out what it meant to be a Muslim, in this environment, was largely regulated by the hadith, the traditions concerning the Prophet and his companions, which became central to Islamic education and religion. View gives a very detailed account of how the hadith were transmitted and used, how both transmission and use changed over time, and how they came to be compiled in books rather than in oral tradition --- a change, he notes, that seems to have first taken root in Iran. Lots of the customs and institutions that became broadly characteristic of Muslim societies were, on Bulliet's account, products of "the edge", these frontiers of conversion, and especially Iran. These began to spread more broadly, he says, only after the process of conversion in Iran was largely complete, on the far side of the century or so when most of the conversions happened. Thus for instance the earliest madrassas founded outside Iran, for instance, were heavily loaded towards having Iranian professors, or non-Iranians who were themselves the immediate students of Iranian scholars.

- Of all this, I will just say that it sounds very plausible, but it's far beyond my competence to evaluate. §

- First book first. Biographical dictionaries were, interestingly enough, a widely-cultivated genre in many pre-modern Islamic countries. Each of these would give a large number of biographies of people (usually men) who were eminent or remarkable in some respect, such as religious scholars in a particular city or district. Part of those biographies would of course be the full name of the figure, which, in Arabic, included a chain of patronymics, of the form "A, the father of Z, the son of B, the son of C, ... the son of M". (Thus the pioneering social scientist generally known in English as "ibn Khaldun" was more properly 'Abd-ar-Rahmân Abû Zayd ibn Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldûn, 'Abd-ar--Rahmân, the father of Zayd, the son of Muhammad, the son of Muhammad, the son of Khaldûn.) Bulliet's starting point is to suppose that the first appearance of an Arabic and especially of a Quranic name in this chain marks the family's conversion to Islam. (As a Persianist, he knows very well that later Muslims had little compunction about naming their children, say, Rustam or Tahmina.) Since the biographical dictionaries give dates, at least dates of death, with some reassonable-sounding guesses about the length of generations, typical age of conversion, and so on, this lets him work backwards to the approximate date of conversion of each patrilineage. (Since the same biographical dictionary will often contain multiple entries for relatives, one would want to (i) cross-check conversion dates, and (ii) only count each conversion once; I believe Bulliet does so but I can't find the passage.)

- Andrew Elfenbein, The Gist of Reading

- An attempt to synthesize what psychologists know about how people read today, and especially what they remember of what they read, with literary-critical concerns about how they should read, and literary-historical interests in how people have read. As an outsider to all the disciplines involved, I found it fascinating, and a model of engaged, modest interdisciplinarity. §

Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur; Pleasures of Detection, Portraits of Crime; Enigmas of Chance; Data Over Space and Time; Writing for Antiquity Islam; Biology; Scientifiction and Fantastica; The Commonwealth of Letters; The Progressive Forces; Tales of Our Ancestors; The Beloved Republic; Heard About Pittsburgh PA; Minds, Brains, and Neurons; Philosophy; Commit a Social Science

Posted at April 30, 2020 23:59 | permanent link