In which Dunning-Krueger meets Slutsky-Yule, and they make music together

Attention conservation notice: Over 2500 words on how a psychologist who claimed to revolutionize aesthetics and art history would have failed undergrad statistics. With graphs, equations, heavy sarcasm, and long quotations from works of intellectual history. Are there no poems you could be reading, no music you could be listening to?

I feel I should elaborate my dismissal of Martindale's The Clockwork Muse beyond a mere contemptuous snarl.

The core of Martindale's theory is this. Artists, and still more consumers of art, demand novelty; they don't just want the same old thing. (They have the same old thing.) Yet there is also a demand, or a requirement, to stay within the bounds of a style. Combining this with a notion that coming up with novel ideas and images requires "regressing" to "primordial" modes of thought, he concludes

Each artist or poet must regress further in search of usable combinations of ideas or images not already used by his or her predecessors. We should expect the increasing remoteness or strangeness of similes, metaphors, images, and so on to be accompanied by content reflecting the increasingly deeper regression toward primordial cognition required to produce them. Across the time a given style is in effect, we should expect works of art to have content that becomes increasingly more and more dreamlike, unrealistic, and bizarre.Eventually, a turning point to this movement toward primordial thought during inspiration will be reached. At that time, increases in novelty would be more profitably attained by decreasing elaboration — by loosening the stylistic rules that govern the production of art works — than by attempts at deeper regression. This turning point corresponds to a major stylistic change. ... Thus, amount of primordial content should decline when stylistic change occurs. [pp. 61--64, his emphasis; the big gap corresponds to some pages of illustrations, and not me leaving out a lot of qualifying text]

Reference to actual work in cognitive science on creativity, both theoretical and experimental (see, e.g., Boden's review contemporary with Martindale's work), is conspicuously absent. But who knows, maybe his uncritical acceptance of these sub-Freudian notions has lead in some productive direction; let us judge them by their fruits.

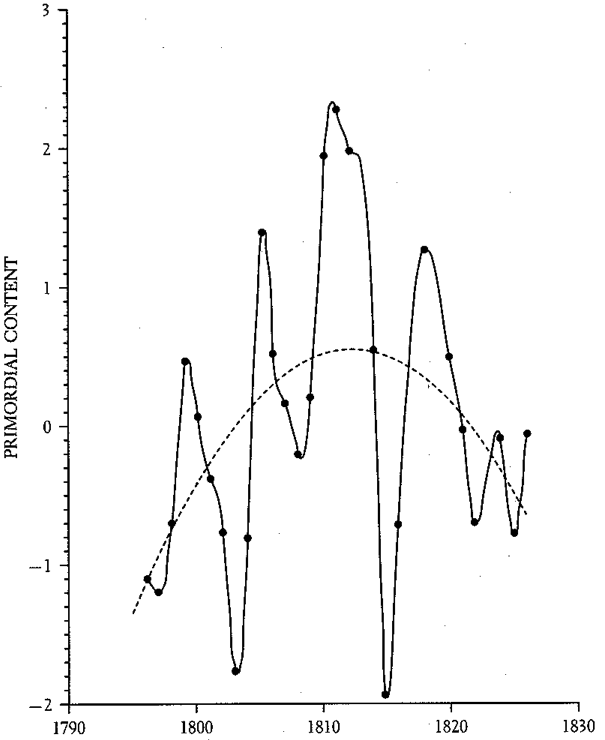

Here is Martindale's Figure 9.1 (p. 288), supposedly showing the amount of "primordial content" in Beethoven's musical compositions from 1795 through 1826, or rather a two-year moving average of this.

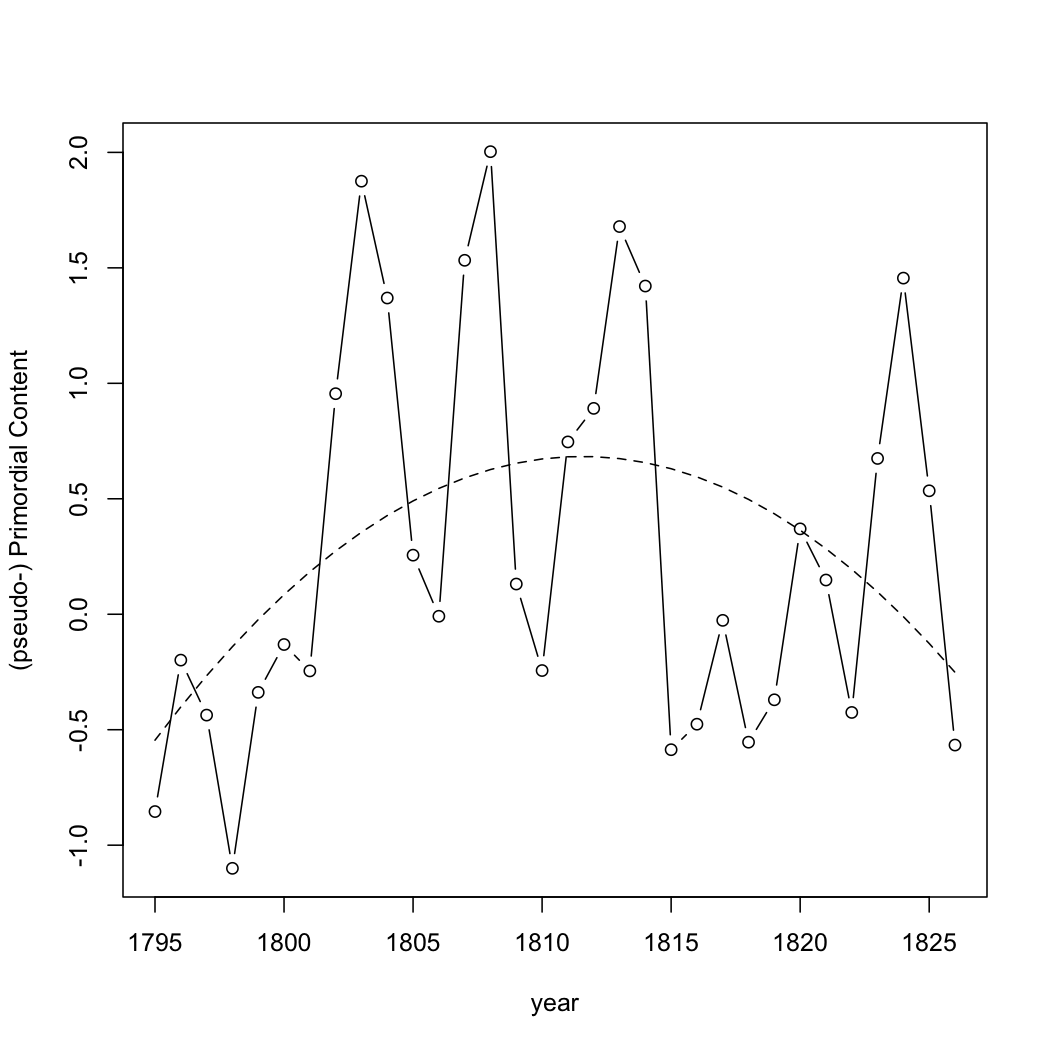

Now, here is the figure which was, so help me, the second run of some R code I wrote.

What is going on here? All of the apparent structure revealed in Martindale's analysis is actually coming from his having smoothed his data, from having taken the two-year moving average. Remarkably enough, he realized that this could lead to artifacts, but brushed the concern aside:

One has to be careful in dealing with smoothed data. The smoothing by its very nature introduces some autocorrelation because the score for one year is in part composed of the score for the prior year. However, autocorrelations introduced by smoothing are positive and decline regularly with increase lags. That is not at all what we find in the case of Beethoven — or in other cases where I have used smoothed data. The smoothing is not creating correlations where non existed; it is magnifying patterns already in the data. [p. 289]

What this passage reveals is that Martindale did not understand the difference between the autocorrelation function of a time series, and the coefficients of an autoregressive model fit to that time series. (Indeed I suspect he did not understand the difference between correlation and regression coefficients in general.) The autoregressive coefficients correspond, much more nearly, to the partial autocorrelation function, and the partial autocorrelations which result from applying a moving average to white noise have alternating signs — just like Martindale's do. In fact, the coefficients he got are entirely typical of what happens when his procedure is applied to white noise:

Small dots: Autoregressive coefficients from 1000 runs of Martindale's analysis applied to white noise. Large X: his estimated coefficients for Beethoven.

I could go on about what has gone wrong in just the four pages Martindale devotes to Beethoven's style, but I hope my point is made. I won't say that he makes every conceivable mistake in his analysis, because my experience as a teacher of statistics is that there are always more possible errors than you would ever have suspected. But I will say that the errors he's making — creating correlations by averaging, confusing regression and correlation coefficients, etc. — are the sort of things which get covered in the first few lessons of a good course on time series. The fact that averaging white noise produces serial correlations, and a particular pattern of autoregressive coefficients, is in particular famous as the Yule-Slutsky effect, after its two early-20th-century discoverers. (Slutsky, interestingly, appears to have thought of this as an actual explanation for many apparent cycles, particularly of macroeconomic fluctuations under capitalism, though how he proposed to reconcile this with Marx I don't know.) I am not exaggerating for polemical effect when I say that I would fail Martindale from any class I taught on data analysis; or that every single one of the undergraduate students who took 490 this spring has demonstrated more skill at applied statistics than he does in this book.

Martindale's book has about 200 citations in Google Scholar. (I haven't tried to sort out duplicates, citation variants, and self-citations.) Most of these do not appear to be "please don't confuse us with that rubbish" citations. Some of them are from intelligent scholars, like Bill Benzon, who, through no fault of their own, are unable to evaluate Martindale's statistics, and so take his competence on trust. (Similarly with Dutton, who I would not describe as an "intelligent scholar".) This trust has probably been amplified by Martindale's rhetorical projection of confidence in his statistical prowess. (Look at that quote above.) — Oh, let's not mince words here: Martindale fashions himself as someone bringing the gospel of quantitative science to the innumerate heathen of the humanities, complete with the expectation that they'll be too stupid to appreciate the gift. For many readers, those who project such intellectual arrogance are not just more intimidating but also more credible, though rationally, of course, they shouldn't be. (If you want to suggest that I exploit this myself, well, you'd have a point.)

Could there be something to the idea of an intrinsic style cycle, of the sort Martindale (like many others) advocates? I actually wouldn't be surprised if there were situations when some such mechanism (shorn of the unbearably silly psychoanalytic bits) applies. In fact, the idea of this mechanism is much older than Martindale. For example, here is a passage from Marshall G. S. Hodgson's The Venture of Islam, which I happen to have been re-reading recently:

After the death of [the critic] Ibn-Qutaybah [in 889], however, a certain systematizing of critical standards set in, especially among his disciples, the "school of Baghdad". ... Finally the doctrine of the pre-eminence of the older classics prevailed. So far as concerned poetry in the standard Mudâi Arabic, which was after all, not spoken, puristic literary standards were perhaps inevitable: an artificial medium called for artificial norms. That critics should impose some limits was necessary, given the definition of shi`r poetry in terms of imposed limitations. With the divorce between the spoken language of passion and the formal language of composition, they had a good opportunity to exalt a congenially narrow interpretation of those limits. Among adîbs who so often put poetry to purposes of decoration or even display, the critics' word was law. Generations of poets afterwards strove to reproduce the desert qasîdah ode in their more serious work so as to win the critics' acclaim.Some poets were able to respond with considerable skill to the critics' demands. Abû-Tammâm (d. c. 845) both collected and edited the older poetry and also produced imitations himself of great merit. But work such as his, however admirable, could not be duplicated indefinitely. In any case, it could appear insipid. A living tradition could not simply mark time; it had to explore whatever openings there might be for working through all possible variations on its themes, even the grotesque. Hence in the course of subsequent generations, taste came to favor an ever more elaborate style both in verse and in prose. Within the forms which had been accepted, the only recourse for novelty (which was always demanded) was in the direction of more far-fetched similes, more obscure references to educated erudition, more subtle connections of fancy.

The peak of such a tendency was reached in the proud poet al-Mutanabbi', "the would-be prophet" (915--965 — nicknamed so for a youthful episode of religious propagandizing, in which his enemies said he claimed to be a prophet among the Bedouin), who travelled whenever he did not meet, where he was, with sufficient honor for his taste. He himself consciously exemplified, it is said, something of the independent spirit of the ancient poets. Though he lived by writing panegyrics, he long preferred, to Baghdad, the semi-Bedouin court of the Hamdânid Sayf-al-dawlah at Aleppo; and on his travels he died rather than belie his valiant verses, when Bedouin attacked the caravan and he defended himself rather than escape. His verse has been ranked as the best in Arabic on the ground that his play of words showed the widest range of ingenuity, his images held the tension between fantasy and actuality at the tautest possible without falling into absurdity.

After him, indeed, his heirs, bound to push yet further on the path, were often trapped in artificial straining for effect; and sometimes they appear simply absurd. In any case, poetry in literary Arabic after the High Caliphal Period soon became undistinguished. Poets strove to meet the critics' norms, but one of the critics' demands was naturally for novelty within the proper forms. But such novelty could be had only on the basis of over-elaboration. This the critics, disciplined by the high, simple standards of the old poetry, properly rejected too. Within the received style of shi`r, good further work was almost ruled out by the effectively high standards of the `Abbâsî critics. [volume I, pp. 463--464, omitting some diacritical marks which I don't know how to make in HTML]

Now, it does not matter here what the formal requirements of such poetry were, still less those of the qasidah; nor is it relevant whether Hodgson's aesthetic judgments were correct. I quote this because he points to the very same mechanism — demand for novelty plus restrictions of a style leading to certain kinds of elaboration and content — decades before Martindale (Hodgson died, with this part of his book complete, in 1968), and with no pretense that he was making an original argument, as opposed to rehearsing a familiar one.

But there are obvious problems with turning this mechanism into the Universal Scientific Law of Artistic Change, as Martindale wants to do. Or rather problems which should be obvious, many of which were well put by Joseph (Abu Thomas) Levenson in Confucian China and Its Modern Fate:

Historians of the arts have sometimes led their subjects out of the world of men into a world of their own, where the principles of change seem interior to the art rather than governed by decisions of the artist. Thus, we have been assured that seventeenth-century Dutch landscape bears no resemblance to Breughel because by the seventeenth century Breughel's tradition of mannerist landscape had been exhausted. Or we are treated to tautologies, according to wich art is "doomed to become moribund" when it "reaches the limit of its idiom", and in "yielding its final flowers" shows that "nothing more can be done with it" — hece the passing of the grand manner of the eighteenth entury in Europe and the romantic movement of the nineteenth.How do aesthetic valuies really come to be superseded? This sort of thing, purporting to be a revelation of cause, an answer to a question, leaves the question still to be asked. For Chinese painting, well before the middle of the Ch'ing period, with its enshrinement of eclectic virtuosi and connoisseurs, had, by any "internal" criteria, reached the limit of its idiom and yielded its final flowers. And yet the values of the past persisted for generations, and the fear of imitation, the feeling that creativity demanded freshness in the artist's purposes, remained unfamiliar to Chinese minds. Wang Hui was happy to write on a landscape he painted in 1692 that it was a copy of a copy of a Sung original; while his colleague, Yün Shou-p'ing, the flower-painter, was described approvingly by a Chi'ing compiler as having gone back to the "boneless" painting of Hsü Ch'ung-ssu, of the eleventh century, and made his work one with it. (Yün had often, in fact, inscribed "Hsü Ch'ung-ssu boneless flower picture" on his own productions.) And Tsou I-kuei, another flower-painter, committed to finding a traditional sanction for his art, began a treatise with the following apologia:

When the ancients discussed painting they treated landscape in detail but slighted flowering plants. This does not imply a comparison of their merits. Flower painting flourished in the northern Sung, but Hsü [Hsi] and Huang [Ch'üan] could not express themselves theoretically, and therefore their methods were not transmitted.The lesson taught by this Chinese experience is that an art-form is "exhausted"when its practitioners think it is. And a circular explanation will not hold — they think so not when some hypothetically objective exhaustion occurs in the art itself, but when outer circumstances, beyond the realm of purely aesthetic content, has changed their subjective criteria; otherwise, how account for the varying lengths of time it takes for different publics to leave behind their worked-out forms? [pp. 40–41]

Martindale seems to be completely innocent of such considerations. What he brings to this long-running discussion is, supposedly, quantitative evidence, and skill in its analysis. But this is precisely what he lacks. I have only gone over one of his analyses here, but I claim that the level of incompetence displayed here is actually entirely typical of the rest of the book.

Manual trackback: Evolving Thoughts; bottlerocketscience

Minds, Brains, and Neurons; Writing for Antiquity; The Commonwealth of Letters; Learned Folly; Enigmas of Chance

Posted at June 30, 2010 15:00 | permanent link